I am in the midst of recovering from a health crisis. After keeping some notes, I started writing. And writing. It got long, and I would love feedback. I will post what I think are the chapters. Here is the prologue.

DISCLAIMER: This is my true story, with minor adjustments for artistic license. To protect their privacy, I have the changed names and biographical details of the individuals depicted. All patients are fictionalized and inspired by my aggregate experience as a physician.

Any views expressed are mine alone, and do not represent the positions of the my employer.

This post is not graphic, but it does describe medical events in the ICU.

When I walked out of the ICU on Sunday, I had no idea how long it would be until I came back. It had been my first week rounding in the ICU in months. My wife had surgery the preceding fall, and we were told the recovery would be rough. We scheduled the surgery for the first of five weeks I had off from clinical responsibilities. It was an unusually long break, but we knew I would be needed at home.

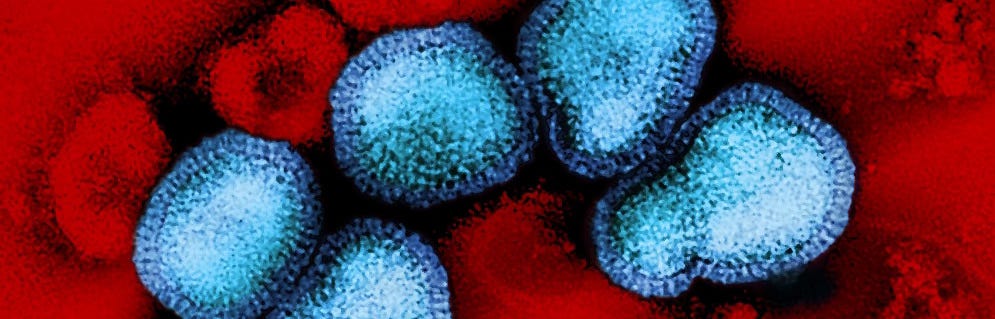

As the associate medical director of the unit, the ICU is my clinical home, and I had missed it. The place of my extended work family, the people with whom I share pictures of my kids, vacation stories, and the emotional highs and lows intrinsic to a career in health care. It had been a week of interesting medicine, working with an enthusiastic team. And caring for many patients critically ill with influenza A.

Nancy did not have the flu. In her sixties and admitted with respiratory failure from an unexplained illness, she was not improving despite two weeks of treatment in the hospital. Throughout her stay, she was surrounded by her extended family and friends. After a long battle with Nancy’s illness, and the clarity that she would not want to live on a ventilator, we extubated her to support from a BiPAP mask. Following days of this support, witnessing her lack of forward progress, her family elected to shift the focus of our care to comfort. Nancy died that week surrounded by loved ones.

Sometimes this sad outcome is the best we can achieve, when it becomes clear that the patient’s destination with aggressive intervention is not likely to be a life they would want to live. Modern medicine can be amazing, and it can also create states of existence that some patients find worse than death. But knowing it is the right choice does not make it easy.

Nancy’s family expressed their gratitude for her care under my watch, brief and ostensibly unsuccessful as it was. Her sister gave me a tearful hug, her brother a firm handshake, and we said goodbye. This is without question the deepest honor of my job—bearing witness to suffering in my patients and their families, and helping them navigate difficult decisions at the end of life. It is a privilege that I do not take lightly.

Sunday was the last of seven days straight working in the ICU. That evening, I didn’t leave the ICU until around 8:30pm. Normally, I would head out just after 6pm.

The night fellow, Jen, told me that a patient was “coming in hot” from the emergency department—a woman in her early forties with respiratory failure.

I texted my wife to let her know I would be late.

Young dying person, sorry I’ll be late tonight

Ok, don’t trip on the play kitchen in the hallway

I knew my four young children would be asleep by the time I got home.

When I walked over to see Lisa after she arrived in the ICU, I realized she was in a room in which another patient had died that morning. It was cleaned and ready for Lisa when the ED needed an ICU bed. It is a strange cycle of life in the ICU, with one patient dying and another critically ill patient following shortly behind. We always need the bed. The usual rituals surrounding the death of another human being are disrupted. “Time of death” is followed by a packet of paperwork, a call to the coroner, and another admission. Rarely is there time to mourn.

There was a crowd outside Lisa’s room. I recognized several night shift nurses, Jen the fellow, and the night resident team. Examining Lisa, I notice her skin was mottled, her blood pressure marginal on high doses of vasopressors running through a left femoral central line, and her oxygen levels low despite us providing 100 percent oxygen. Inspecting the ventilator, I saw signs of a significant lung injury. The labs in the computer showed her liver enzymes were elevated, and her blood was not clotting normally. I looked at the foley catheter. There were a few milliliters of concentrated urine in the tubing but no signs of ongoing urine output—her kidneys were failing along with her other organs.

While the nurses settled her in, with Jen at the bedside in the event of an emergency, I went out to the waiting room, where I knew Lisa’s family was sitting. I introduced myself as the ICU attending physician to two stunned and overwhelmed relatives—Lisa’s sister Patti and brother Mike. I learned Lisa’s boyfriend was at home with their tween daughter.

Patti and Mike were clearly in shock. Patti told me Lisa had been sick. That Lisa had finally agreed to go to the hospital. She had not wanted to miss work during the week, and risk losing her job. Patti and Mike drove Lisa to the hospital. On the way, Lisa stopped breathing. Patti swerved, pulling the car over. She called 911. From there it was a blur.

Patti asked, in a monotone voice, “She’s not going to make it…is she doctor?”

I shared my concern that Lisa was in multiple organ failure. It was immediately life-threatening. I did not know whether she would survive the night.

“If there are friends or family in town who would want to see her, they should make their way to the hospital tonight,” I advised.

I explained that I needed to get back to caring for Lisa, and that the nurses would call her family back when they could come see her. They were in shock, nearly silent as they cried.

“This is a nightmare. I can’t imagine what you are feeling. I am so sorry she and you are going through this.”

“Thank you, doctor,” choked Patti. Mike sat silently, eyes wet.

I walked out of the waiting room, back through the double doors of the ICU, to Lisa’s room. She was on slightly lower doses of the vasopressor medications to support her blood pressure, but that was about the only improvement. I made some subtle changes to the ventilator with Jen to try to optimize things, but it made little difference. Given Lisa’s young age, I called my colleague Ryan, to discuss the possibility of ECMO.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is a machine that does the work of the lungs outside the body when the lungs have failed. Ryan and I had worked together for many years during ECMO evaluations for patients in the Medical ICU. I would trust him to care for my family. He came to see Lisa with me, and we both agreed that while ECMO might improve her oxygen levels, it could do nothing for the multiple other failing organs. ECMO is not a treatment in itself. It must be a bridge to a destination.

It was becoming clear there was only one outcome for Lisa, and ECMO would not help. I left Jen at the bedside after a discussion of a few finer management points for the evening. We both knew that the primary focus should be for Lisa’s family to spend time with her.

Lisa died before midnight. Jen called to let me know. Lisa was just older than me. She was living her life in the world days beforehand. She had a daughter just older than Brandon. The death certificate listed the cause of death as multiple organ failure, with contributing causes from influenza and pneumonia.